For people who don’t know what to say and the people they’re saying it to anyhow.

*

INTRODUCTION

I didn’t almost die—not even close. I didn’t watch my hair fall out in the shower, or have the doctor give me X number of months to live. This is not about how sick I am, or was, or how lucky and grateful I am or you should be. It’s me looking back at the dark tangle that falls in your lap when illness enters your life. And how we cope, or don’t. And flowers.

***

An older couple shuffles into the infusion center. The man is ruddy-cheeked, with a red V-neck sweater and new loafers. He’s holding his wife’s oversized pocketbook. She is nicely dressed, with a colorful scarf tied over her balding head. The nurse is getting her settled into the reclining chair next to mine.

“I can go get you a coffee,” he tells her.

“I don’t need coffee,” she says.

And then, after a pause: “Well what do you want me to do, just sit across from you and watch you get the chemo?” He says the chemo as if it’s a new age treatment her sister insisted she try out.

She doesn’t say anything. The nurse is trying to act like she’s not hearing the conversation. I’m looking away with my headphones on but I’m not listening to any music.

*

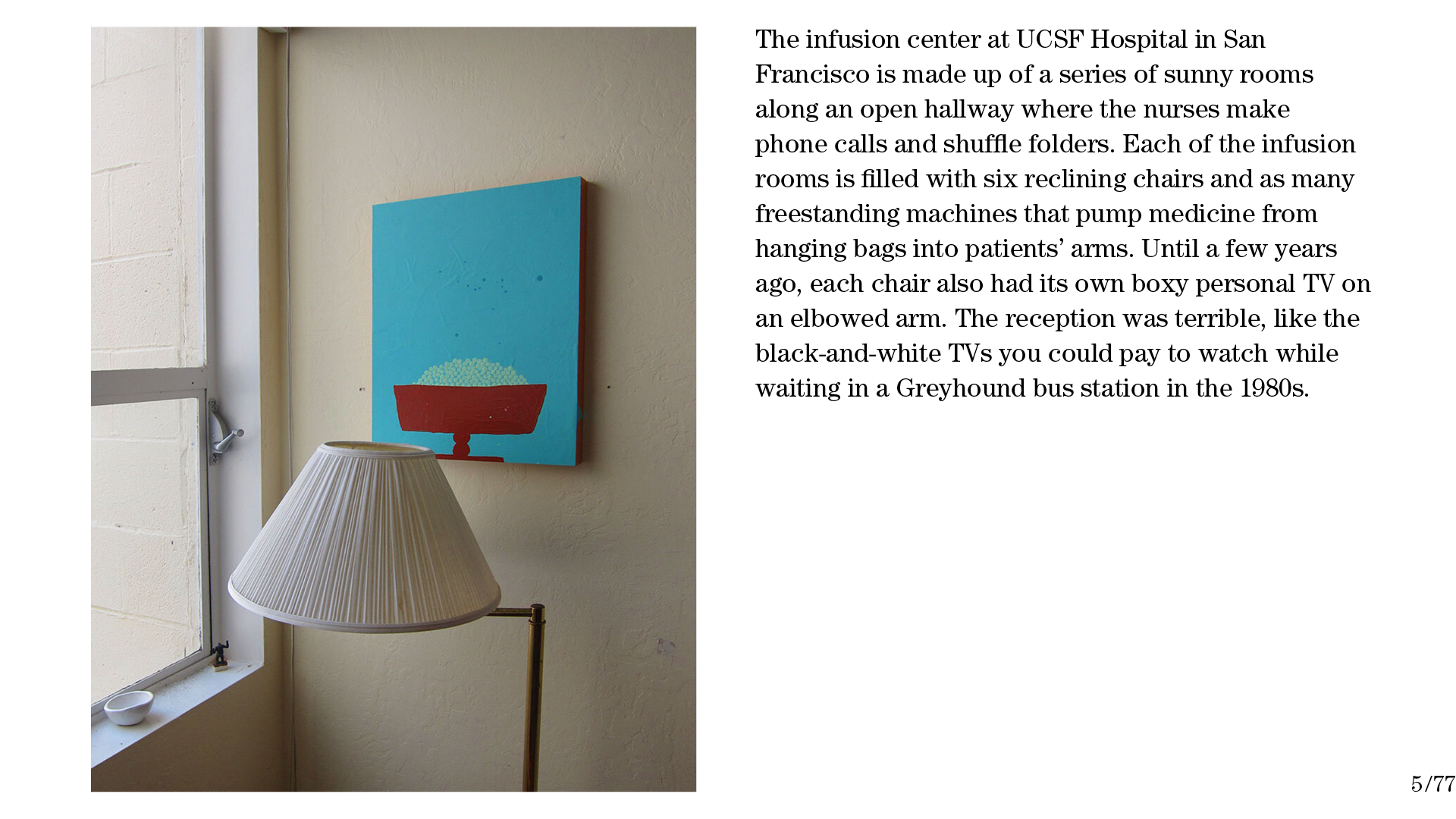

The infusion center at UCSF Hospital in San Francisco is made up of a series of sunny rooms along an open hallway where the nurses make phone calls and shuffle folders. Each of the infusion rooms is filled with six reclining chairs and as many freestanding machines that pump medicine from hanging bags into patients’ arms. Until a few years ago, each chair also had its own boxy personal TV on an elbowed arm. The reception was terrible, like the black-and-white TVs you could pay to watch while waiting in a Greyhound bus station in the 1980s.

*

When it matters most—when someone we love needs our support—it seems most of us don’t know what to say. And worse, when we don’t know what to say, we tend to say things that only add to the burden. We are talking through our feet, always on the verge of putting them in our mouths. This seems like a system-wide failure of humans.

*

When I first got sick, I was a 28-year-old graduate student studying Chinese art history, living in a small apartment in Connecticut with a spastic kitten named Henry. At first nobody knew what was going on. My digestive system was suddenly out of commission, like an engine seizing up in a car. I was hospitalized for several weeks while the doctors tried to settle on a diagnosis. Some rare virus from my travels in Western China? A ruptured spleen?

Some days I couldn’t even watch college basketball on the hospital television—seeing men in their prime exerting that much energy was too tiring. Every day had periods like getting held underwater by a wave, unbearable but then okay again. When I woke from sleeping, there was that brief moment of re-remembering my shitty situation: Still in a hospital gown, still can’t eat. Still held under.

Eventually they figured out that I had Crohn’s disease, an autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation in the intestines. Or ulcerative colitis. Or both. I had never heard of any of it. All I knew was that I was fine and then out of nowhere I wasn’t fine at all. This thing had landed on me from the inside.

*

Flowers are a secret language nobody really knows how to speak.

*

My mother, it so happens, was an award-winning flower arranger. She could assemble a beautiful combination of branches and buds in a jar the way some people can throw together a delicious meal from what looks like an empty refrigerator. Our kitchen smelled like flowers because there were always buckets of them in the sink.

It was odd when people sent flowers to my mom on an occasion of celebration or grief. They always looked fake in comparison to what she could put together. When she was in the hospital a few years back, her bed was surrounded by garish arrangements of pink and yellow from FTD and the like. Of course the intent was kind, but did the arrangement also say something about their relationship? Who sent the white plastic basket of daisies wrapped in gold Mylar? I presented each arrangement to my mom in her hospital bed and jettisoned the rejects to the nursing station. It’s not that she was offended—I think she was genuinely touched—she just had really strong feelings about flowers in vases.

*

At first I made the mistake of thinking that the more people who knew about my illness, the more help I would have. But instead I just had to field the onslaught of concern and contradicting advice. My aunt recommended not eating vegetables anymore. An old friend said I should absolutely get acupuncture, while in the hospital if necessary. She knew a great woman in New Mexico. Someone else said I should drink only aloe juice. I should start smoking cigarettes. No, only eat vegetables. Get the surgery right away, it worked for a friend’s cousin. Nothing spicy. Eat anything at all, it really doesn’t matter. Just not lettuce. And don’t eat peanut butter because the oil is always rancid and rancid oil is bad for my gut. Do not let them do surgery of any kind. Have I considered getting in better shape? No stress, this condition comes from people who can’t handle stress and so do not stress about anything because it’s only going to make it worse. Sometimes spicy foods can help.

*

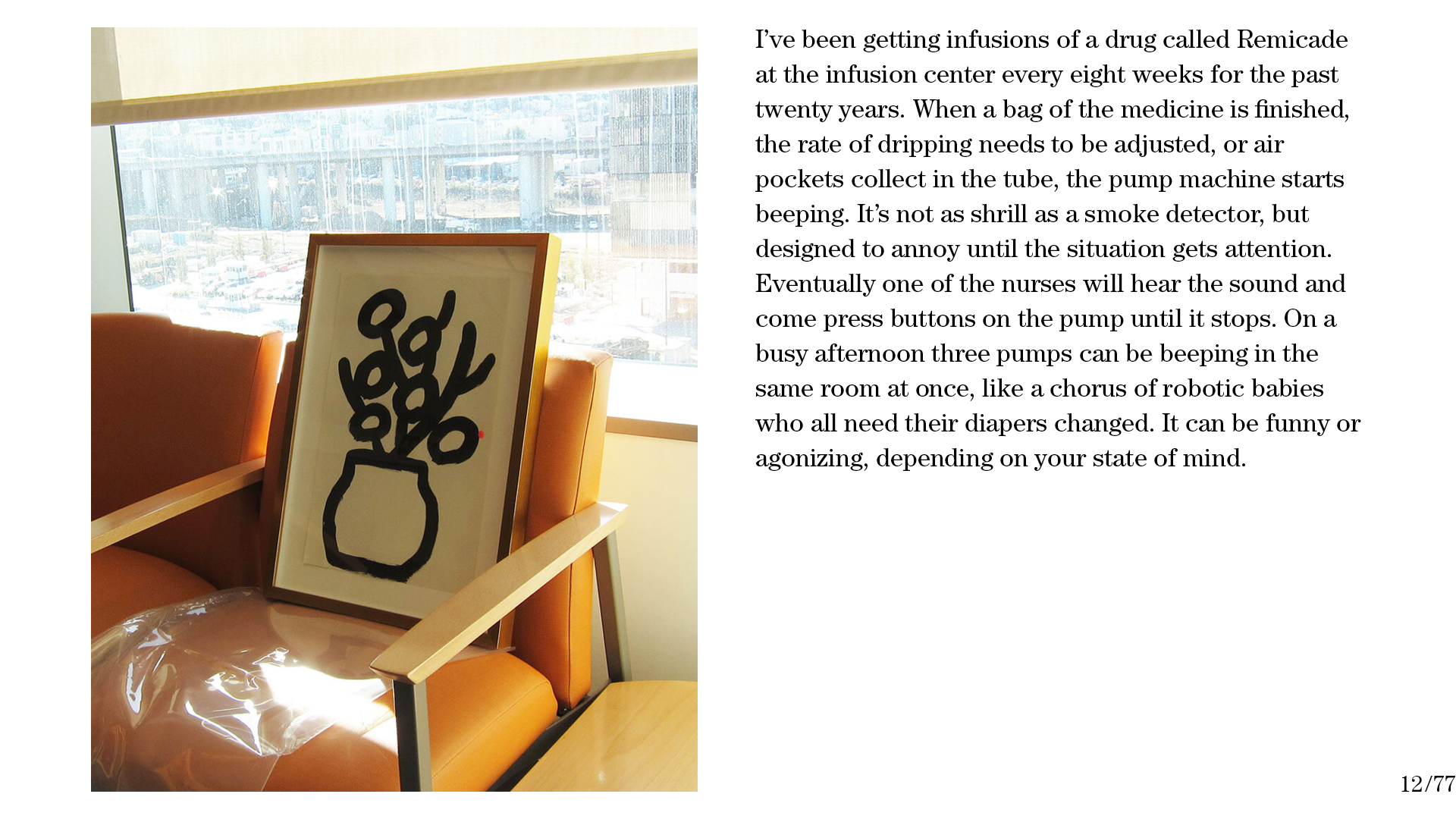

I’ve been getting infusions of a drug called Remicade at the infusion center every eight weeks for the past twenty years. When a bag of the medicine is finished, the rate of dripping needs to be adjusted, or air pockets collect in the tube, the pump machine starts beeping. It’s not as shrill as a smoke detector, but designed to annoy until the situation gets attention. Eventually one of the nurses will hear the sound and come press buttons on the pump until it stops. On a busy afternoon three pumps can be beeping in the same room at once, like a chorus of robotic babies who all need their diapers changed. It can be funny or agonizing, depending on your state of mind.

*

Most of the people I see in the infusion center are much sicker than I am. They are getting some form of chemotherapy with medicines that sound like a language from the future. I assume almost everyone else is dealing with cancer but I can’t tell what body parts are affected. What I can see is that everyone is fighting. They are fighting with their wigs, fighting with their out-of-season winter hats, fighting with the help of their friends or moms or daughters. Most people are fighting by themselves. They’re in a fight for their lives, while I’m mostly fighting for my quality of life. Still, it feels good to do it together, even if we rarely say a word.

*

After a few weeks of being really sick, I could see that this wasn’t the kind of situation that gets better on its own, like the flu or a broken bone. I had a debilitating disease that has no cure. It felt like everything about my life would be different, like a line had been permanently crossed. I knew it wasn’t going to kill me, but it didn’t feel like I was going to live very well either. My life had taken a turn, away from everyone else, into the dark.

*

Nothing was working. Eventually I was put on a torturous course of Prednisone. The drug made me crazy and my face got round and puffy. Friends I hadn’t seen in awhile didn’t recognize me. The smallest inconveniences brought on surges of rage in me. Most nights I had nightmares, or terror-filled insomnia, hopelessly waiting for daylight. I wanted off of the Prednisone more than I wanted to get better, but it was the only available tool to shut down the inflammation.

*

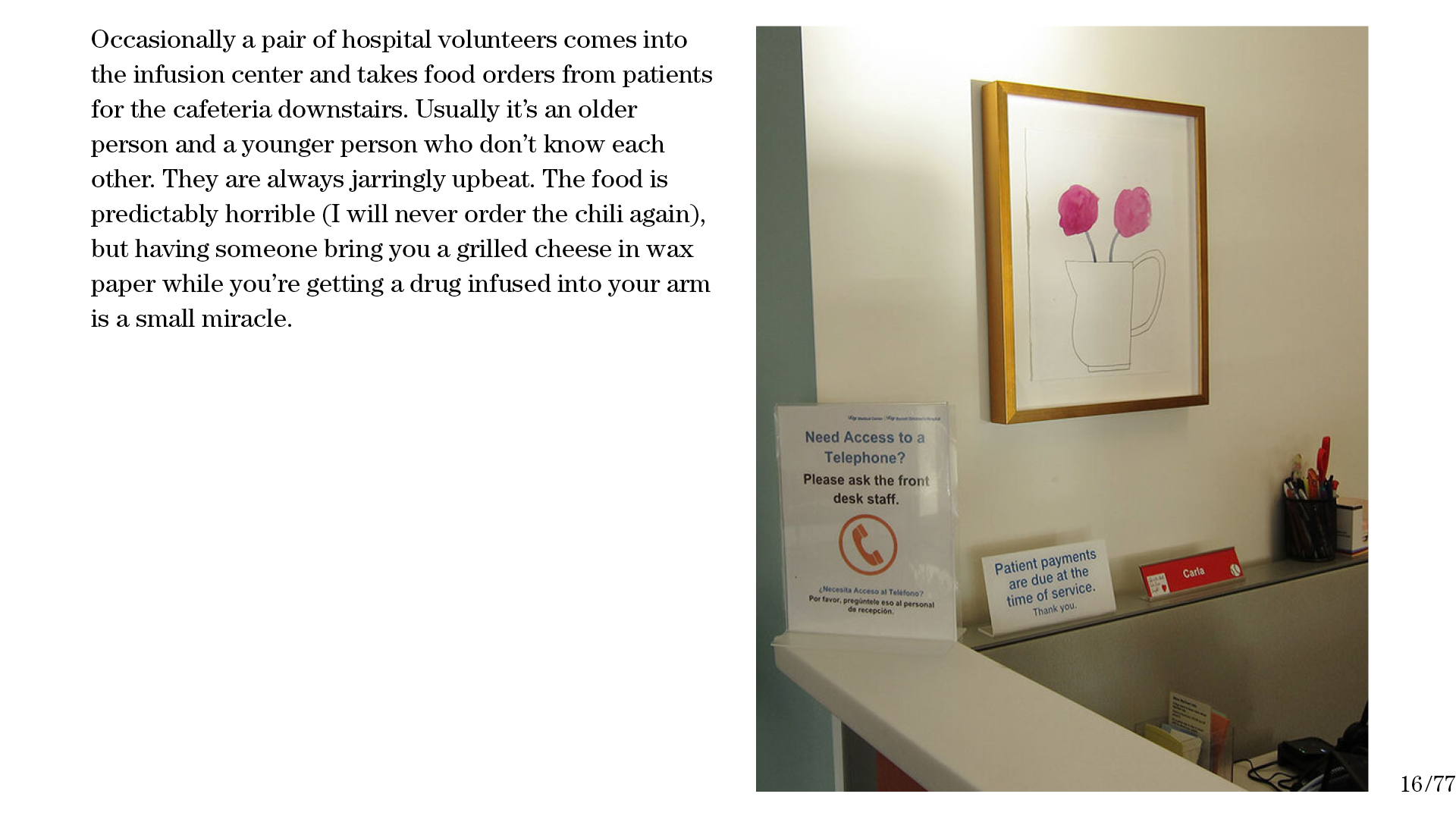

Occasionally a pair of hospital volunteers comes into the infusion center and takes food orders from patients for the cafeteria downstairs. Usually it’s an older person and a younger person who don’t know each other. They are always jarringly upbeat. The food is predictably horrible (I will never order the chili again), but having someone bring you a grilled cheese in wax paper while you’re getting a drug infused into your arm is a small miracle.

*

People have been painting flowers for as long as there have been paintbrushes. Before that, they must have used their fingers. Flowers are just the right amount of content—beautiful in form, ambiguous in meaning.

The same flowers can say really different things. Congratulations. I’m sorry. I love you. I can’t believe you’re dead. They are full of potentially strong, unnamed emotions. And then they wilt, fade, and get thrown in the bin.

Art is the same way. You can mean a lot of different things when you make a painting, but ultimately it holds only what the viewer sees in it. The artist is simply the first part of the expression, like shouting into an empty cave.

*

Sometimes I talk to other patients while we are hooked up to our pumps. As on airplanes, I usually wait until near the end of my time there, in case the person is overly eager to talk. But nobody has seemed crazy yet. Our conversations are simple: What are you in for, what’s that like, isn’t this place weird? Like any tribe, there’s immediate shared knowledge among patients here, a sense of family almost, but also solitary and separate. It’s odd to share something so intimate with strangers for a couple hours and then never see them again. The infusion center isn’t church and it’s not a social club, and after all these years, I’ve never made a friend there. But I like getting my medicine with other people. It’s like riding an elevator with a group of strangers, all heading to the same floor.

*

Tips for navigating the infusion center:

Schedule your infusion early in the morning, when the rooms are quiet and there are fewer delays. Bring a baseball hat and earphones to retreat into. Have the nurse stick the IV into the arm on whatever side of the chair the pump will end up. Ask them to use paper tape on your skin instead of the sticky plastic kind that pulls out arm hair. (Or, if they have it, the self-clinging veterinarian’s tape.) When you go to the bathroom, watch the tubes and the power cord on the pump—getting tangled is annoying but getting the tube stuck on the door handle while you walk back to your chair can be jarring. There’s a second bathroom around the corner that’s usually open.

They can magically warm blankets for you. Learn the nurses’ names; you’ll see them again. There’s a drawer full of graham crackers and saltines in the waiting area if you’re that hungry. Take as many as you want.

*

My friend Roger fielded frequent distress calls from me during my year on crazy-making Prednisone. I called him mostly because he was the only person I felt OK showing just how bad things were. And because he gave the best coaching on how to deal with it: Shrink your time frame. The more acute the suffering, the shorter the time you should be trying to get through. So when things are just kind of shitty, just try to get through the day. But when it’s excruciating, and you want to break windows or pour coffee on your keyboard, aim for a thirty-second endpoint. And then another. Also, down in a hole is a horrible spot to make any important decisions in your life. It’s a place you need to simply endure, trusting that eventually you’ll get back to the surface where you can look around and think of what you need to do next. So don’t go quitting your job, or telling off your landlord. Just go thirty seconds. And then five minutes. An hour. Make it to bedtime. Don’t do anything besides whatever you have to do to get to the next day. It won’t feel like this forever. (But it will probably feel like this again.) (But don’t think about that right now.)

*

I haven’t been especially sick for years. I’m in what my doctor recently called “deep remission,” which, when he said it, felt like having my probation lifted. I’m mostly fine these days.

Eventually though, I’ll be facing illness again in some way. We all will. Unless some other, scarier tragedy strikes first. Sickness isn’t something that makes us special. It’s not something that happens to a few of us. It just looks that way because it doesn’t appear on a schedule, and we prefer not to think about it.

*

Over the ages, different flowers have conveyed critical messages among queens, spies and lost lovers. This kind of tulip, that color rose. A certain number of willow branches. I’m convinced world history has been shaped by these coded messages in ways nobody realizes.

*

My friend Laura was visiting a neighbor who has breast cancer. “Please take this away,” her friend said, pointing at a Tupperware container marked CANCER SOUP. “A friend keeps bringing it, and she insists it’s filled with all the right healing ingredients. But I don’t want any fucking Cancer Soup!” Laura took it home and said it was delicious.

*

Orient your experience toward the nurses. They are your allies—let the other relationships fill in around them. Nurses are generally the only people who know what to say to you. The doctor’s job is to figure out what’s happening. Your family members are supposed to love and worry about you. But the nurses run the show.

People who can’t see the heroic value of nurses are imbeciles. It wouldn’t be a big stretch to imagine a hospital where nurses get paid the most and everyone else is considered a highly trained specialist or manager.

*

I’ve had two different doctors make the case to me that I have brought this illness on myself. That may be true, but both times they said it as if they were annoyed that I was sick and taking up their time. I left them both and finally found a doctor who knows how to talk to me. He gives me disappointing news from time to time, but it’s never from a position of power or judgment.

The only thing I would bug a very sick friend about is to find a doctor you trust and who respects you. Some doctors are jerks, and some are saints. The last thing you want to deal with when you’re ill is testing out doctors, but until you find a good match, it will be hard to feel like you’re in position to start to get better. Ask someone for help with the search, but somehow push yourself until you feel like you’re in good hands. Everything else you can slack on.

*

When I’m finished at the infusion center, I usually walk to a bathhouse down the street in San Francisco’s Japantown. Going from hot tub to sauna to steam room to cold plunge seems to counter whatever effects the drug is having that day. Or maybe it doesn't do anything. Either way, all that soaking and sweating makes me look forward to infusion days. It’s become an accidental ritual, the second half of getting the medicine. Doctor’s orders.

*

I have shat my pants more times than I care to recount. At work. On a bus. Outside a friend’s apartment. In a greenhouse. Every time it has been so humiliating that my only impulse is to flee. And not just flee the greenhouse, but really want to flee everything, to just skip this part of my life until sometime later, when I’m back in clean clothes and the old ones are in a garbage can somewhere.

It hasn’t happened for many years now, but looking back now I feel like, What was I supposed to do, really? This is what happens when you get this disease. Sometimes you crap your pants. Raising a baby helps because you get comfortable wiping shit off of whatever surface it has found its way onto. And then you carry your child back to the pile of blocks on the floor and notice how cute she looks in that hand-me-down sweatshirt from her cousin.

*

The best thing anyone ever gave me while I was in the hospital was a coffee table book about people eating bugs around the world. The photos were revolting in a way that didn’t have much effect on me, given that I wasn’t eating any food. An old friend from high school brought it to me. He and I rarely talked about my illness when he visited, but he was one of the only people who brought his sense of humor into my hospital room. I had left mine behind long ago. Now that I’m not sick, the book is disgusting.

*

Apparently Remicade is derived from mouse urine. I haven’t looked into what exactly this means, but I think about it sometimes as I watch the bag drip into the tube attached to my arm. Modern medicine is so much weirder than the old-fashioned medicines we make fun of for being crazy. Splicing this animal bit and connecting it to that plant compound and combining it with the DNA from that sick monkey. It’s beyond comprehension, the alchemy of alchemy.

And of course the pharmaceutical industry is a huge financial scam, fueled by the most powerful lobbies and greedy executives and all of the corporations behind those promotional pens in doctors’ waiting rooms. Johnson & Johnson pulled in nearly seven billion dollars from Remicade in 2016 alone. But it has also made me virtually symptom-free, and helped countless other patients do the same. So thank you to the chemists and the researchers and the sketchy lobbyists. And thank you to the mice for your little dishes of urine. I’m sorry if it turns out they use more than your pee.

*

Wait, no. The best thing anyone brought me in the hospital was that very hyper kitten named Henry that I adopted just before I first got sick. The cat was an absolute terror, and as soon as I got back home I gave him back to the adoption agency. But it was a delight to see Henry appear from under my friend’s coat after she closed the door in my room. He jumped off my bed, ran around in circles and did a few leaps to avoid phantom predators until my friend scooped him up again, just before the nurses came back with their rolling carts.

*

Right now you have several pounds of bacteria, viruses and fungi living inside you. In your body there are more of these foreign cells than there are human cells. You are the host to their sophisticated, mysterious ways. Altogether they weigh about the same as your brain, and you’d be dead without them. The study of this microbiome is one of the most promising areas of medicine these days.

In my case, my body sees some of these microbes as intruders and sends white blood cells to fight a battle with them. Falsely accused, the “intruders” fight back, and the ensuing conflict leads to inflammation. My immune system, the overseer of threats to the body, can’t learn the difference, so the drugs I take try to shut down the process that leads to the fight. This is as much as I understand about the workings of an autoimmune condition like Crohn’s disease.

*

I’m not sure about the whole “if it doesn’t kill you it makes you stronger” idea. But I do think going through some really awful health stuff gives you a good idea of who your friends are.

*

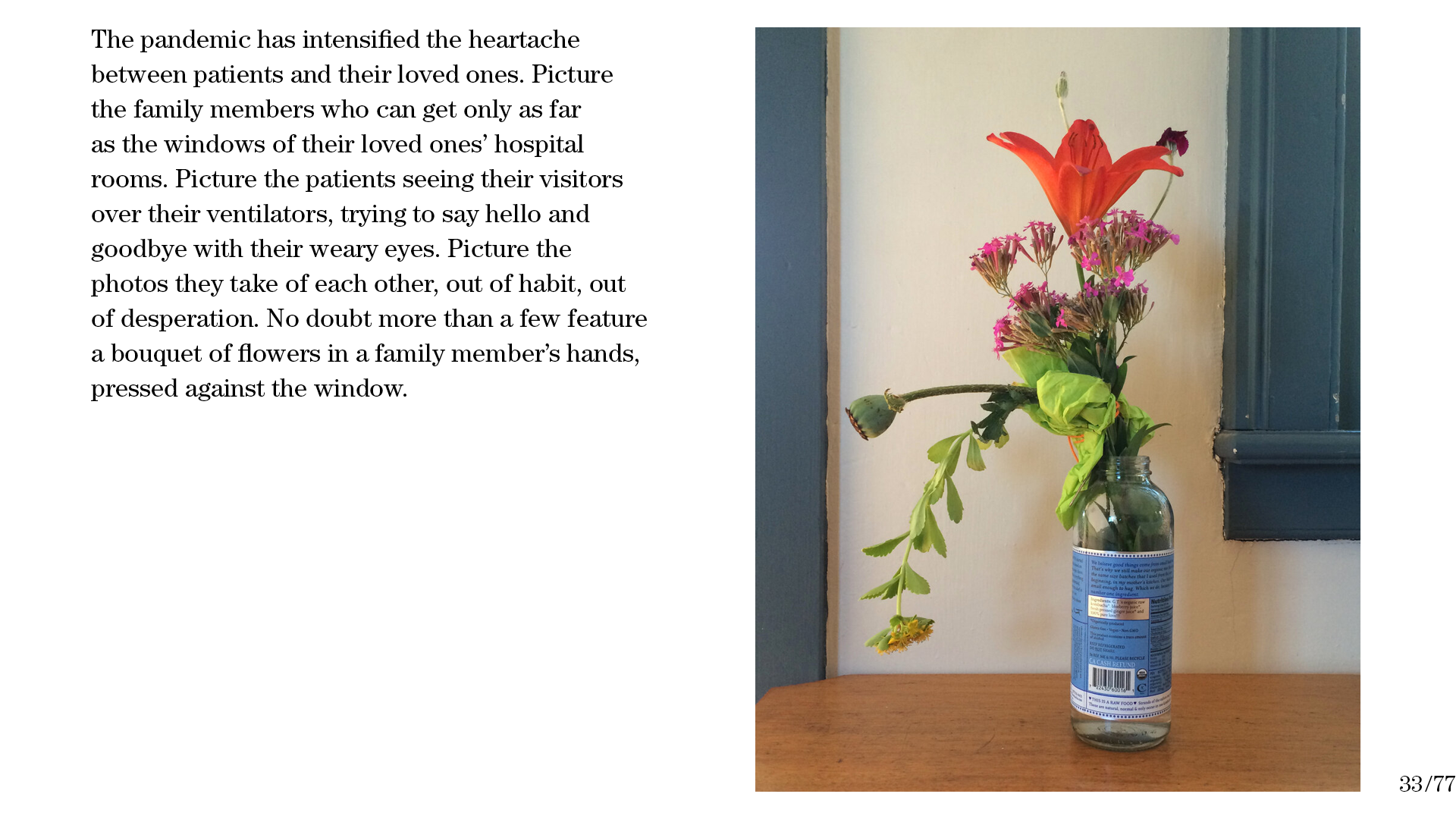

The pandemic has intensified the heartache between patients and their loved ones. Picture the family members who can get only as far as the windows of their loved ones’ hospital rooms. Picture the patients seeing their visitors over their ventilators, trying to say hello and goodbye with their weary eyes. Picture the photos they take of each other, out of habit, out of desperation. No doubt more than a few feature a bouquet of flowers in a family member’s hands, pressed against the window.

*

Most of the details of my symptoms during a flare-up aren’t worth getting into. I’ll just say that when it’s bad, there’s near constant diarrhea, oftentimes with blood. For some reason the blood is the part nobody can handle, including me, even after all this time. It’s like the screaming lights of an ambulance in my rear view mirror. But blood is blood and nobody seems too freaked out by a bloody nose. Still, blood means this is not that stomach bug that’s going around. It’s the opposite of EUREKA.

*

Evelyn is a nurse at the infusion center I’ve never met before today. She looks at me with motherly eyes and puts her hand on my shoulder as she introduces herself. While she’s preparing to stick the IV needle in my wrist, she tells me how she’s from Ghana, and has a few grown children also practicing medicine in different countries. When I look down, I’m confused to see the IV connected and taped in place. I felt nothing. Some nurses have secret powers.

*

Walking into the steam room at the Japanese spa after my infusion, the hot mist is so thick I can’t see anyone. As my eyes adjust, I vaguely make out an older man lying on a tile bench by the door. He has a large branch of bay leaves that he’s vigorously brushing against his chest while he takes deep, loud breaths. Like it or not, we are all experiencing the healing power of his aromatherapy. Eventually I can see he’s wearing a wool winter hat but is otherwise naked like the rest of us. I can barely tell how many other people are in here, but I sense an easy tolerance among the group.

*

When you need them, blood transfusions are a kind of instant strength you can feel only because you’ve been so weak. At times I’ve needed several. I’ve wondered, whose blood was it that is now a part of me? A victim of some horrible car accident, or a kind college student who stopped at the bloodmobile on her way to economics class?

Late one night in my hospital room, an unusually tall nurse came in to set up my first transfusion. I fell asleep as the bag of blood started flowing into my arm. After an hour or so I woke up to a feeling of wetness, and when I opened my eyes there was blood everywhere—I was covered in it. Was it mine or the unknown stranger’s? I called for the nurse, and after she started to fiddle with my IV, the blood started spurting in all directions like a hellscape oil well: onto my face, onto the floor. I could taste it on my lips. The nurse was visibly in shock too, but before long she got it working smoothly and walked out. A chaotic storm had burst into the room, and then it was over. Hospitals are really good at cleaning up messes, and when I woke up in the morning I wondered if I had dreamt the whole scene.

*

Holiday decorations in the infusion center make me sad. Halloween cutouts dangling from the ceiling, tinsel and metallic balls hanging from the television screens. I know they’re meant to bring the outside world in, to add some cheer, but they don’t. Is it possible they’re doing something when I’m not noticing them? Could the tiniest part of my soul be opening up in response to these cheap ornaments? Or maybe they are for people other than me.

*

I’m lying on the floor next to my bed at home. My gut is hot with pain. I’m moaning and moving around, trying to find a position that doesn’t hurt, but there’s no place to go. My whole body feels swallowed by it, my mind too. What has happened to my life that I’m suddenly swimming in this all-over pain? I’m momentarily aware of how dramatic everything feels.

Out of nowhere, I remember some advice I heard about heading directly into the pain instead of trying to stop it. I have no idea how to do this. I’m cursing whoever told me about this idea under my breath. It’s like trying to go toward a train crash while you’re in the middle of it.

Now my wife, Lisa, is here. She’s trying to help, but what can she do? Invisible pain stabbing at your insides is hard for someone else to tend to. We’re in different worlds. Eventually the discomfort subsides—actually, I don’t remember that part—and I crawl up off the floor and into bed, and fall asleep in my clothes. Lisa helps take off my pants and my sweater. I do remember that—I woke up while she was doing it and thought, you saved me.

*

The best visitors at the hospital know how to bring our relationship into the room with them and let it play out. Some know how to land a joke in such a humorless place. Others sit and watch television with me, feeling no need to fill the air with conversation. Some aren’t afraid to tell me about whatever is happening in their worlds, even if it seems trivial to both of us.

The very best of them know how to talk to the nurses to improve my situation. With so little energy, I can hardly understand how the hospital systems work. It’s nearly impossible to be a patient and direct your own care at the same time. Especially when the moment you finally fall asleep, someone walks in with a rolling cart of gadgets to gather data. I will always remember my friend Liz, who cornered the head nurse to coordinate the cart visits so they were bunched together. You’d think sleep is the one thing everyone at a hospital would be trying to facilitate, but it doesn’t work that way.

*

There’s a vase of fake flowers strapped to the base of a tree on a winding road near my house. When I drive by it at night, my headlights light up the pink and orange petals like dayglo popcorn. Flowers as a desperate response—she died right here, and you were just about to drive by thinking this is just like every other stretch of road.

*

Most of the tests are beyond unpleasant. The stuff they make you drink, the machines they put you into, the tubes they stick inside wherever they say they need to go. Like the various drugs they give you, most of them make your symptoms worse. I totally get it—they need the info. But some of these machines are barbaric.

*

Generally speaking, “I know how hard this is for you” doesn’t make people feel better because they know it’s not true.

*

After a few more bouts of the terrible cramping, I read a bit more about this idea of heading straight into the pain. The next time it comes on, I try focusing on the discomfort. It fucking hurts!

I try a different tack, taking stock of all of my body parts. I’m marginally relieved to realize that the tips of my fingers don’t hurt at all. Or any part of my hands for that matter. My shoulders and arms and neck feel fine, as do a wide range of other body parts. But wow, does the left side of my stomach throb and burn. While the pain itself is unchanged, for a moment I’ve broken the conclusion that my whole body is engulfed.

*

Flora works at the infusion center, and is almost always there to take my vital signs before I settle in to start my medicine. She’s a diehard San Francisco Giants fan, adorned with as many team logos and colored pins as she can squeeze onto her scrubs. We always catch up on the latest scores or off-season trades. Her enthusiasm is directed at the baseball team, but it spills over onto the patients, too. Sometimes being around people who are excited about anything can make you feel like everything’s going to be okay.

*

Of all of the desperate people I’ve seen in their chairs getting their medicine, I can’t recall a single person crying.

*

An elderly woman slowly makes her way into the infusion room with her grandson. I think they are Vietnamese. The woman sits down in the recliner across from me, and the nurse asks the young man questions about her symptoms. How is she feeling since her last dose of chemo? How many times a day is she going to the bathroom? How watery is her diarrhea? Her grandson is translating diligently, and I’m feeling the discomfort of everyone in the room. I want the little shower curtain thing to become a soundproof chamber where they can all cry or shout or do whatever the situation calls for. Instead the nurse says, “I’ll be back in a minute,” and stops at the sanitizer dispenser on the way out.

*

Of all the alternative therapies I have experimented with—recommended or otherwise—something called “guided imagery” has been the only one that stuck. My training lasted just three sessions, but I still use it regularly years later. I was blessed with a remarkable teacher named Michael Cantwell, who was trained in Western and traditional medicines. We hit it off immediately. The gist of guided imagery, at least in my case, is that people with recurring illness tend to struggle with their own perceptions of themselves as either sick or healthy. It’s nearly impossible to believe that wellness is a reality when you are very sick, just as it’s hard to access the sickness when everything’s okay. We tend to see ourselves as either debilitated or totally fine. This makes coping with each new recurrence difficult because it feels like it’s happening to us from out of nowhere.

More importantly, when we start to get symptoms, we tend to inadvertently accelerate the process until we are so sick we can stop dealing with all of the anxious decision-making and instead just be a patient.

To counter these habits, Dr. Cantwell taught me to burn into my mind an image of myself as a healthy person that was so vivid and accurate that I couldn’t discard it as soon as the first symptoms came along. I’m not a sick person. I’m not a healthy person, either. I’m a mixture of the two, even now that my disease is in remission. I can access this vision of my robust health at any time and put it up against whatever symptoms I’m experiencing. When it’s working, I remember that I’ve always eventually returned to an energized, relaxed and healthy state. So far.

*

These days I eat pretty much whatever I want. I try to steer clear of processed foods and toward the kinds of real ingredients Lisa cooks at home. When I get sick, though, I mostly stop eating altogether. Food irritates my inflamed gut, and not eating gives it a chance to heal. I used to drink a lot of canned nutrition drinks, which at first tasted like milkshakes but after a while were more like sweet spoiled milk. When I was at my sickest, I received nutrition through a tube that went straight into a nozzle in my torso. In bed at night, I would hook up to a black backpack and let the cloudy liquid flow straight into my body, like water irrigating a potted plant. For a short while there, I was part machine. Occasionally, I’d wake up tangled in tubes.

*

I’m driving over the Golden Gate Bridge one morning on the way to the infusion center for my medicine. It’s a perfect, sunny day and the water is sparkling as a cargo ship heads off to somewhere in Asia. In the air I notice a piece of paper that looks like money. For a moment it lands on my windshield. Other cars are moving fast on all sides, and now we are driving through a cloud of dollar bills, like the aftermath of a surreal pillow fight. I can’t make out the denominations, but I can see it’s real currency. Nobody can stop to gather any of it up on account of our collective speed. Some of the bills get run over, others flutter over the side of the bridge.

This actually happened, but I don’t know what it means.

*

The training for guided imagery goes like this: I sit in a chair facing Dr. Cantwell. I relax and take a few breaths. The lights are dim, and he asks me to describe a place where I have felt especially full of energy and robust health. I begin talking about an outboard motorboat I used to drive off the coast of Maine, my first real feeling of freedom. I’m twelve or thirteen. I describe the boat itself, what the air feels like, and the sun. The smell of salt water and the sound of the engine. The patterns of the wake when I look back at the water behind the boat. Soon I’m recounting details that seem beyond memory, like the exact shape of the fingered grooves in the steering wheel. I can feel my bare feet touching the textured grip on the boat’s floor. Somehow I can feel my shins and my knobby knees. I’m kind of hungry. My lips are chapped. The details keep coming. I’m building a portal.

*

My mother was back in the hospital in Philadelphia with a dangerous infection that set in after knee replacement surgery. I flew into town at night, and in the morning I picked some flowers from the garden at her house. I put them in a jar from the kitchen and drove to see her. At the hospital, a man at the reception area directed me to her room, then stopped me before I set off to find it.

“Sorry, we can’t have real flowers in the patients’ rooms.”

“Can I at least show them to my mom?” I asked.

He half nodded, willfully ignoring my question. I headed to the elevator, sheepishly holding the jar at my side.

*

The other kind of therapy I can recommend is therapy. I don’t need to know anything about you to guess that it would improve your life to look at how you came to be who you are, and how that has been steering your ship without your knowing it. You will only get out what you put in, and sometimes you will wish you never started. If you’ve been waiting for a nudge though, let me help: you should probably start seeing a therapist.

*

At my next appointment with Dr. Cantwell, he leads me back into the visualization mode and guides me to describe how I might picture the illness this time. I’m closing my eyes, but I’m not feeling it. I can’t seem to access my guts the way I could with the motorboat.

After a few minutes, I start to picture my intestines, mostly cramped up and dark. I’m visualizing runny food waste sloshing about, colors mixing together like finger paint. I can see a loose, dark wad jammed into one of the main tunnels, blocking my gut. It opens like a hand and is floating in the center of my belly like a jellyfish. It’s a dirty gym sock.

I open my eyes to the reality of the office, and slowly reorient myself. Dr. Cantwell and I look at each other. “What am I supposed to do with that?” I ask.

“You’re an artist,” he says. “Paint a picture.”

*

A woman with curly white hair is cruising down the hallway of the infusion center in an electric wheelchair. She takes a turn and zips toward me as I’m walking to the bathroom with my pump. I can’t tell if she’s a patient or a patient’s mother, but I can see in her eyes that she is feeling the stoke as she speeds by.

*

I don’t know what death is—none of us do. I can only imagine it’s something like birth: mysterious, wrenching, and impossible to remember. Where we go when we die must have some analogy to where we came from when we were born. My daughter came out screaming with life, as if jumping off a rope swing for the first time. The idea of her ever dying makes my spine hurt, but in the big picture, I know one day it will happen. It’s how we get to be alive.

*

When my dad was dying of cancer, he was in a hospital in downtown Philadelphia. The hallway outside his room had a clear view across the river to the building where he worked for decades as the president of a book manufacturing company. Years after the factory relocated out of downtown, the giant NATIONAL PUBLISHING CO. billboard on the roof remained visible. It was an iconic element of the Philadelphia skyline, visible in postcards of the city. Eventually the sign was repainted in the same blue and yellow colors to advertise the loft apartments the building had become.

Over the course of my father’s final days, my brothers and I visited with him every day. A week before he died, we noticed a crane had started to dismantle the billboard. Every day we came to the hospital the billboard was less and less, and so was he. I don’t remember which expired first. It was another contrived scene from the movie we were living.

*

Toward the end of his life, Dad watched a lot of TV. He especially liked a low-budget show about how things are made in factories. I loved watching it with him. It showed a world where everything is planned out and explainable, straightforward and magical at the same time. “Amazing how they get the mustard into the bottles,” I’d say.

“That’s a lot of mustard,” he’d say back.

Eventually he seemed to not care much about what he was watching. Sports, of course. But also The Weather Channel or a fishing show, despite his lack of fishing experience. As the billboard was coming down across the river from the hospital, Pope Benedict happened to be giving Mass at Yankee Stadium. We put it on the television in Dad’s room, as if we had ordered this religious blessing for him on pay-per-view. None of us could really follow the service, but it was nice to have in the room with us. I could tell he felt something from it—maybe it took him out of the hospital for a moment. The best shots were of everyone in the crowd.

*

The day after the Pope’s Mass, my brothers and I were eating bad cafeteria food at the hospital when we got word that Dad wanted to meet with us. This was unexpected—he was so sick at this point, he couldn’t say much more than a sentence. When we made our way up to his room, he was lying on the bed with the oncologist standing next to him.

“Hi guys,” Dad said. He sat up in his bed and put his glasses on. He looked oddly clear-headed. My oldest brother closed the door. “I wanted you to hear what the doctor just told me.” The oncologist explained how the cancer had spread into more of his body, and that the options were few and not promising. We asked a couple questions, but really there wasn’t much to learn about. The doctor left, and we closed the door again.

Dad looked up at the three of us. He was suddenly leading an important meeting, the way he must have done at work for decades. “I don’t think I want to fight this anymore,” he said. “And I wanted to talk to you guys and see what you think of that.” We looked at him as each of us gave our blessings. Dad was officially dying, and we were all learning that as a group. He told us he wanted to get home, and we agreed to start him in an at-home hospice program. Then he lay back down and fell asleep with his glasses on.

*

My mom and I were lying on her bed at my parents’ house when I told her about the meeting Dad had called with us the day before. She seemed relieved to not have been there, but I think she felt guilty, too. “I don’t want him to come home,” she said. She didn’t know how to take care of him even with round-the-clock nurses there. She was a mess, suddenly desperate. It was all so ugly and fucked up. I knew how to be around him, but I had no idea how to take care of her. She needed it badly, though. We had seen his death coming for months, and suddenly it felt like we were totally unprepared.

*

The phone rang beside her bed. It was my brother Jon. “Dad just died,” he told me. I don’t remember the rest of the conversation. I hung up the phone and lay there with Mom, holding hands. We stayed like that for an hour or so without saying anything. It was the only meaningful part of taking care of her I can think of.

*

As I get older, it seems like there are always at least a couple of people I care about who are dealing with unsolvable suffering. Right now an old friend is recovering from a rare illness affecting his brain; in all the world, only fifty people have it. A mentor woke up with a disorder that paralyzed part of his body. A teenager I know has been cutting her arms and texting about suicide with her friends.

I tell myself I’m too busy to get involved, but I know it’s not hard to stay in the picture. Make a phone call, pay a quick visit. There is so little we can do to change people’s actual symptoms, but by now I know my job: just don’t let their perception of deep isolation become true. A one-word text that just says Hey can do that. Or I could send flowers. Mostly, though, I don’t.

*

My dad’s remains were delivered to us in a black plastic box the size of a loaf of bread. We buried it in a graveyard on that small island in Maine where I learned to drive the motorboat. After we covered the box with dirt, we wrestled the granite gravestone on top and tried to make it sit flush with the surface of the ground. Our family plot is actually in the woods behind the graveyard, less than 20 yards from the waterline at high tide. At the water’s edge, a short cliff with exposed roots is crumbling into the ocean. I’m told this wooded plot was relatively cheap for my family to claim. With rising sea levels, before long our little boxes will all float out to sea.

But hold on, did we really bury my father in a plastic box? I remember opening the FedEx package with my brothers just before we started digging, and pulling out some kind of plastic container. Weren’t we supposed to transfer his ashes into a brass urn? We could have found a better vessel even in the tool shed back at the house. A mayonnaise jar, maybe. An old tin box from his favorite crackers.

*

Years before, we buried my grandmother in the same place. She was a tomboy all her life, and an avid golfer. As we took turns digging the grave, one of my uncles reached into the hole and pulled out a golf ball with a red stripe across it, caked in dirt. We all laughed and were comforted by the serendipity of the moment. It felt like she was saying hello just as we were all saying goodbye.

With my dad, we found nothing of the sort. But I remember talking to him the summer before, in the very spot where we eventually buried him.

“How does it feel to come here, Dad?” I asked.

“Well at least I know where I’ll be for a while,” he replied.

It was an awkward moment. We didn’t hug or cry or talk about it further. But it was real, and I could tell we both felt changed. He wasn’t coming back here alive, and I supposed, in time, somehow that would be okay.

*

I don’t remember anything about the flowers from Dad’s memorial service. I doubt Mom had time to put them together, but they were still probably very nice. The truth is that Dad wouldn’t have remembered them either. He didn’t care about flowers. He spent decades helping my mom load buckets of them into the station wagon, or tethering a finished arrangement to a cardboard box for the trip to a church for a wedding. If he disliked helping her, he never showed it. She just as easily could have been obsessed with fancy chickens—he would have happily built little coops for the fuzzy chicks. Flowers were simply there. We had a lot of hockey equipment lying around the house, too.

*

From their perspective, of course, flowers are nothing more than advertisements for bees and other pollinators. Their beauty is entirely biological. Most blossoms are bursting with ultraviolet designs we can’t even see. To a bumblebee, each flower is a psychedelic party den.

*

I’m awake in the middle of the night. My gut is cramping for the first time in years. I hope it’s not a big flare-up coming on, that I won’t end up back in the hospital. My mind is racing and I’m trying to conjure up the guided imagery motorboat vibes. It’s not working very well, but at least it’s something to do.

As I finally begin to fall back to sleep, an image appears in my mind of a big hole in the ground. It’s a hazy hallucination, oddly pleasant to watch it appear, like in a movie. For a moment I can feel myself awake and asleep at the same time, and then I’m fully unconscious and the image is more complete: I’m in the woods, standing next to a giant hole, throwing flowers into it. Other people come and do the same. It all feels scary, but it’s what needs to happen. The flowers fall and fall into the darkness and disappear. I think it’s okay to throw some other things in there, too.

*

Two women come into the infusion center. They are dressed almost identically in stylish gray-on-gray sweatsuits. I can’t tell which one is going to get in the chair. In a way it doesn’t matter because once the patient is all set up, her partner snuggles up next to her and they spend the next two hours together watching a movie on an iPad.

*

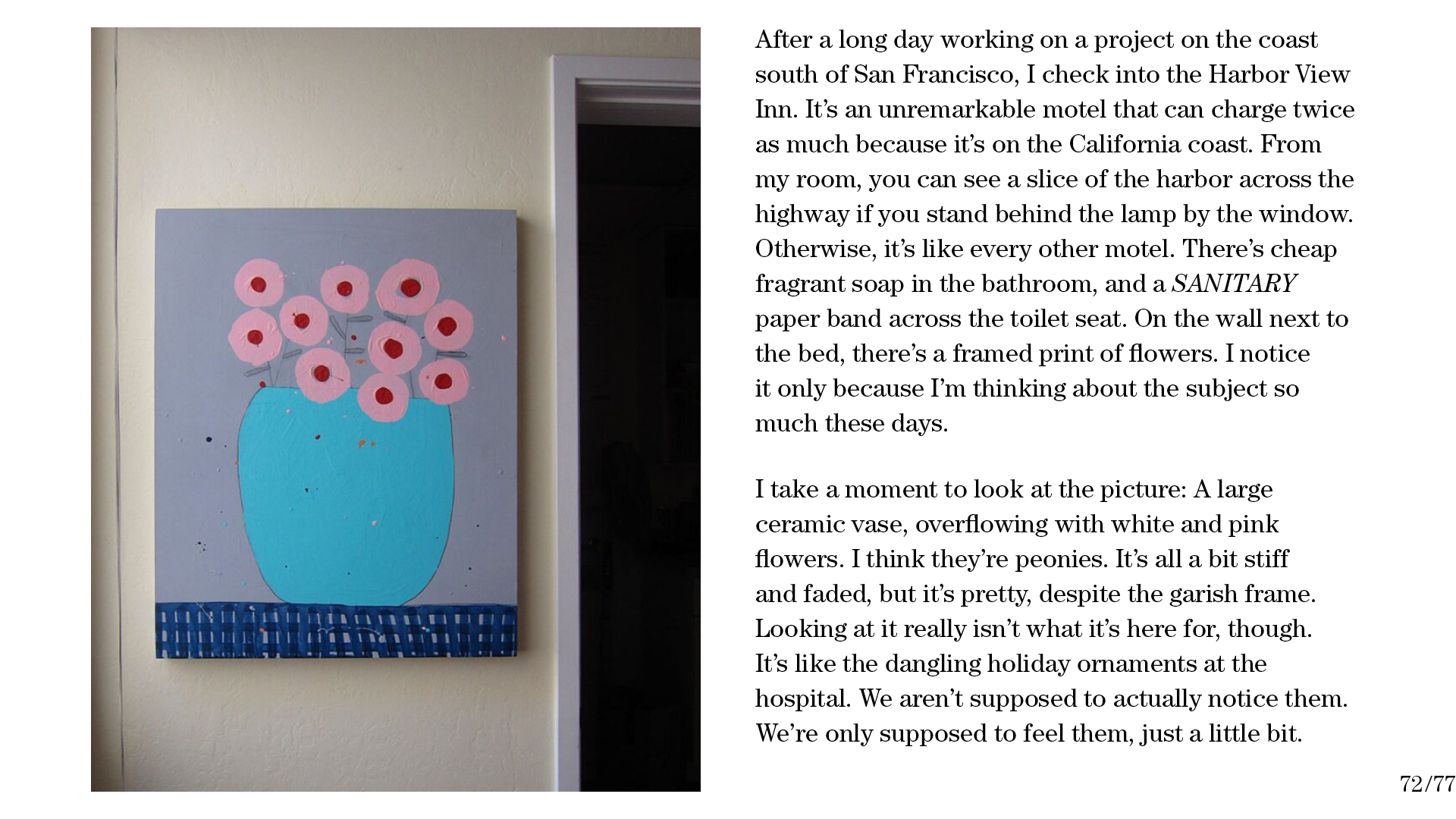

After a long day working on a project on the coast south of San Francisco, I check into the Harbor View Inn. It’s an unremarkable motel that can charge twice as much because it’s on the California coast. From my room, you can see a slice of the harbor across the highway if you stand behind the lamp by the window. Otherwise, it’s like every other motel. There’s cheap fragrant soap in the bathroom, and a SANITARY paper band across the toilet seat. On the wall next to the bed, there’s a framed print of flowers. I notice it only because I’m thinking about the subject so much these days.

I take a moment to look at the picture: A large ceramic vase, overflowing with white and pink flowers. I think they’re peonies. It’s all a bit stiff and faded, but it’s pretty, despite the garish frame. Looking at it really isn’t what it’s here for, though. It’s like the dangling holiday ornaments at the hospital. We aren’t supposed to actually notice them. We’re only supposed to feel them, just a little bit.

*

So far I’ve recovered each time I’ve had another flare-up. When it’s happening, though, it always feels like trying to get through something impossibly hard, with no guarantees. None of us knows how to handle anything besides trying to endure whatever is in front of us. Sometimes passing time is an act of bravery.

If you are reading this and you’re sick, I’m sorry. I hope you can find a way to experience the whole situation, and not just what’s so horrible about it. Maybe a nurse will say something genuinely nice to you, or your sister will come and watch bad TV with you this afternoon. Maybe your toes don’t hurt. Maybe you want to scream. Or maybe what I’m saying here isn’t helping at all—it’s more gaudy flowers from someone who doesn’t know what to say. I still say the wrong thing all the time. That’s human nature, too.

*

A few months before my father died, I drove with him to the hospital for a chemotherapy treatment. A nurse set him up in a tiny private infusion room. The pump was perpetually in the way, and I couldn’t get the sound on the TV to work. I offered to get him the newspaper or coffee, but he didn’t want anything. So we just sat there. At one point, I went out to talk to the nurses, but there was nothing about his care that needed discussing.

When the infusion was over, we made our way to his car on the roof of the hospital parking lot. It was a bright spring day, and Dad was wearing a red winter jacket he didn’t need. I suddenly noticed his baggy jeans, how his belt was cinched in and buckled into a newly punched hole. He had a light covering of dandruff sprinkled over him and the lenses of his glasses were filthy. I felt my stomach drop. He went to get in the driver’s seat, but I stepped in front of him.

“I’ll drive, Dad.”

He looked at me. “OK,” he said. “I can get in myself.”

He shuffled around to the passenger side, settled into his seat, and closed the door. I helped buckle the seat belt over his jacket, and we drove home.

END

AUTHOR’S NOTE

For many of us, being sick can be an overwhelming test of isolation. I created Flowers In The Dark in part because when I first got sick, I couldn’t find any resources that could convince me I wasn’t going crazy.

If you know someone who might benefit from reading this, please share it. It is intentionally free for anyone to access.

Thank you to everyone who has supported this project—and my health—over the years. There are far too many people to name here.

Tucker

*

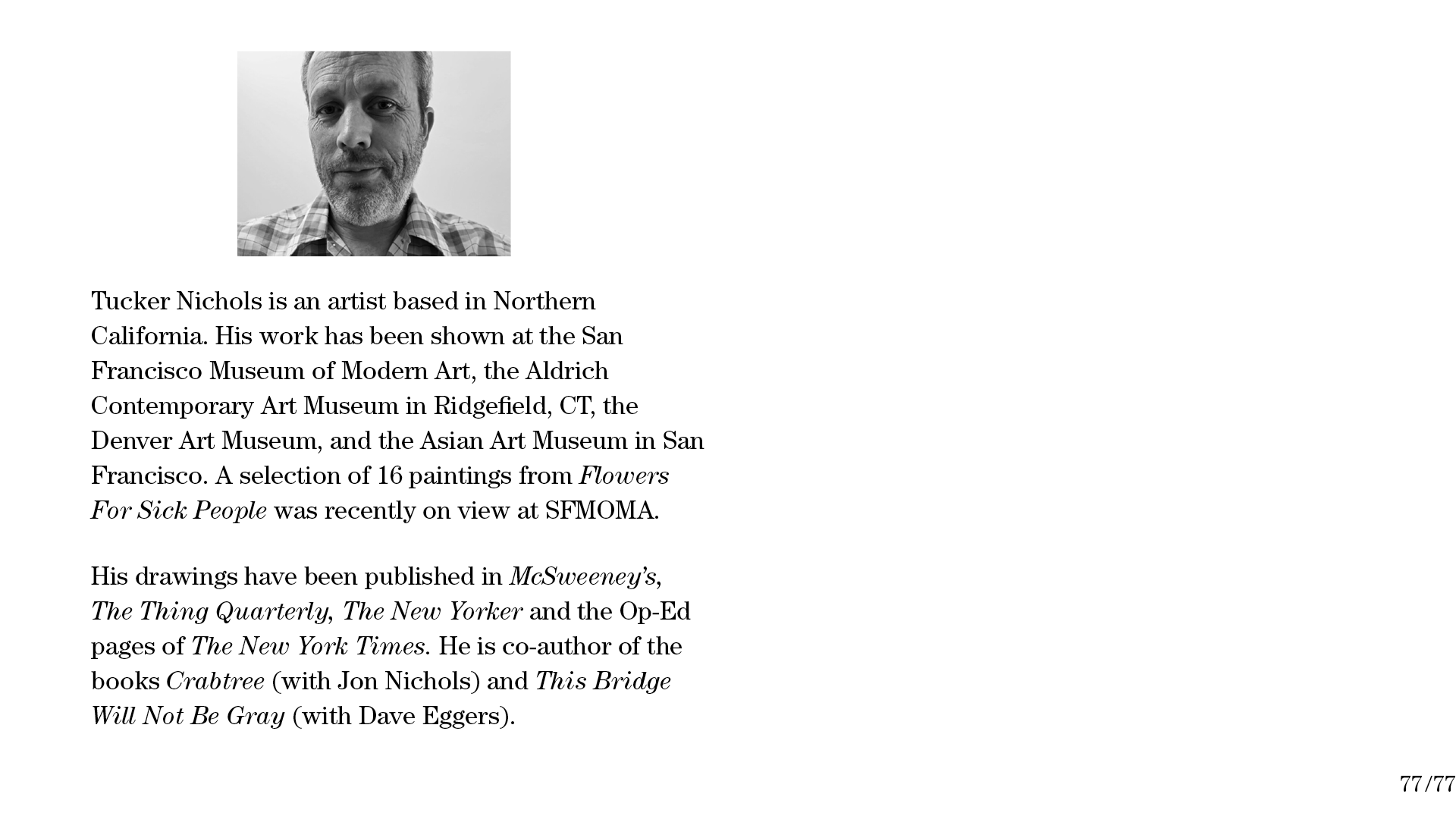

Tucker Nichols is an artist based in Northern California. His work has been shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT, the Denver Art Museum, and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. A selection of 16 paintings from Flowers For Sick People was recently on view at SFMOMA.

His drawings have been published in McSweeney's, The Thing Quarterly, The New Yorker and the Op-Ed pages of The New York Times. He is co-author of the books Crabtree (with Jon Nichols) and This Bridge Will Not Be Gray (with Dave Eggers).

You can see more at www.tuckernichols.com.